J. Sibiga Photography/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Ian Musgrave, University of Adelaide

Scents, fragrances, perfumes. These words transform the mere concept of odours into something more evocative. Fragrance is intimately linked with our memories and feelings.

For me the heavy smell of eucalyptus is forever associated with summer. A waft of its scent and my mind brings up the feeling of heat and the buzzing of cicadas. Kate Grenville shares a similar reminiscence of her mother’s perfume in her latest book, The Case Against Fragrance.

So why a case against? As Grenville writes, “Surely only a weirdo wouldn’t enjoy the smell of flowers and pine forests?”

But consider those to whom fragrances bring blinding headaches, asthma attacks and allergies. Something like a third of all Australians have adverse reactions to fragrance, with nearly 8% so severe that the people involved have lost work days.

Grenville builds the case that fragrance is having a significant adverse impact in modern society through personal anecdote and peer-reviewed research. On the way she takes us through the multitudinous things that fall under the term “fragrance”: how we perceive it, who regulates (or fails to regulate) its components, who tests it for safety, and how we can share the air together, fragrance fans and foes alike.

Readers may be puzzled. We have been using fragrances for thousands of years: how could something so ubiquitous be harmful? Surely we would have noticed before now? But let me remind you that we used toxic white lead as a cosmetic for centuries before realising its harms.

Grenville points out that many of the natural essential oils that form the basis of fragrances have adverse or toxic effects that have only recently been recognised. The properties that make the chemicals in fragrances able to vaporise easily and stimulate our sense of smell also mean that many are highly reactive and able to stimulate immune reactions.

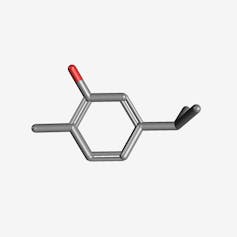

Ian Musgrave, Author provided

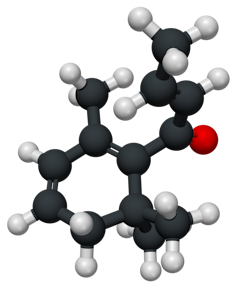

One example is carvacrol, the chemical that gives oil of oregano its distinctive scent. It can also chemically react with proteins to stimulate an immune response. β-damascenone, whose chemical structure looks like an industrial hazard, is a natural compound found in rose essential oils and Kentucky bourbon (it is safe at fragrance concentrations, but can cause allergic reactions). 1,8-cineol, which is part of the distinctive smell of eucalyptus, can cause liver damage if you consume enough of it.

Grenville shows that with modern processes fragrances are more available than ever before. Whereas in the past perfumes were expensive items used only occasionally outside those well-off, fragrances are now everywhere, not only in perfumes but in air fresheners, detergents and laundry liquids to name a few places we find them.

The rise of synthetic fragrances has the advantage of low cost and less need to use animals. (We no longer need to extract musk from the glands of civets.) But this ubiquitous use and higher concentration of fragrances means that more people are exposed to fragrances for longer than ever before.

Grenville smoothly charts this rise, and the regulatory and safety issues. Fact-dense and extensively referenced, the book is a delight to read and never gets bogged down. I may be biased, of course, by my love of chemistry.

Ian Musgrave, Author provided

While some of the science has been simplified, the book generally conveys the sense of it correctly. I particularly salute Grenville for working through the labyrinth that is Australia’s National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme (you can find the NICNAS section on cosmetics here). The issue of regulation is a thorny one, given the current mood of government is for less, but the book gives a good walk-through of the regulatory and testing issues. Anyone who can write about NICNAS without inducing somnolence is a master indeed.

While the issues around fragrance and headaches, respiratory issues and allergies are well documented and supported, the issues around hormone (or endocrine) disruption are less clear. There is evidence that high concentrations of some of the essential oils that make up fragrances (and other non-odoriferous components that go into fragrances) can activate hormone receptors. But these compounds are hundreds to thousands of times weaker than our natural hormones.

Grenville gives diethyl stilboestrol (DES), used in therapy, as an example of how endocrine disruptors can affect health. But DES is very potent, hundreds to thousands of times more potent than the weak hormone mimics in fragrances and cosmetics. This could give people a misleading impression of the risk associated with fragrances. We’ve seen similar discussions about phthalates found in cosmetics.

Statements such as, “We know about the dangers of endocrine disruptor bisphenol A in our plastic water bottles,” are unhelpful because they are basically untrue, based on exaggeration of risks.

Nonetheless the issues around other risks, regulation and fragrance in the workplace are well developed and thoughtful. Read The Case Against Fragrance and you will never think about fragrance in the same way again. If you have been suffering fragrance in silence, you will know you are not alone.

Ian Musgrave, Senior lecturer in Pharmacology, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Michellina Van Loder is a Professional Writer, Journalist, Web Designer and Blogger at Labyrinth Press where she shares her and others tales about trail blazing the way out of the Labyrinth of Chemical Sensitivities and Mould, here, down under in Australia. Oh, and we share the latest news, resources, research, and opinion on MCS, EHS, CIRS and related.

Thank you, this is great! It makes a difference when it comes from high profile people rather than just the ordinary person who is affected. I’ll be passing it on.

Yes, it’s exactly the type of awareness we need. Kate Grenville is a highly respected author with many other amazing books under her belt. She’s said in interviews she wouldn’t have been as susesful if she had of been able to go out whenever she liked. I have more coming with her in it.